Thanksgiving

Our brother admits he’s homesick so we pan toward the raw turkey

and simmering onions, smile, crowd ourselves into the phone

like a family advertising a network plan. Then Mom waves a scrap

of butcher paper at the screen, gives the annual decontamination

lecture. The dogs watch through windows, beg at every door.

We divide our work. I set the table and think inhospitable thoughts;

you chat and wash, help me slip from rooms to avoid our guest’s

smug advice. I skin vegetables. Sometimes gratitude is enough,

sometimes blood is not. We roll out pies and accept our dead

as they interrupt. Today’s a holiday from our usual autonomy.

The girls shriek and demand to be spun in circles. Forever, do

again. We eat. The youngest wants to flip backward, to be lifted

up. When you set her down, she pretends to knock us over—

we play along and fall.

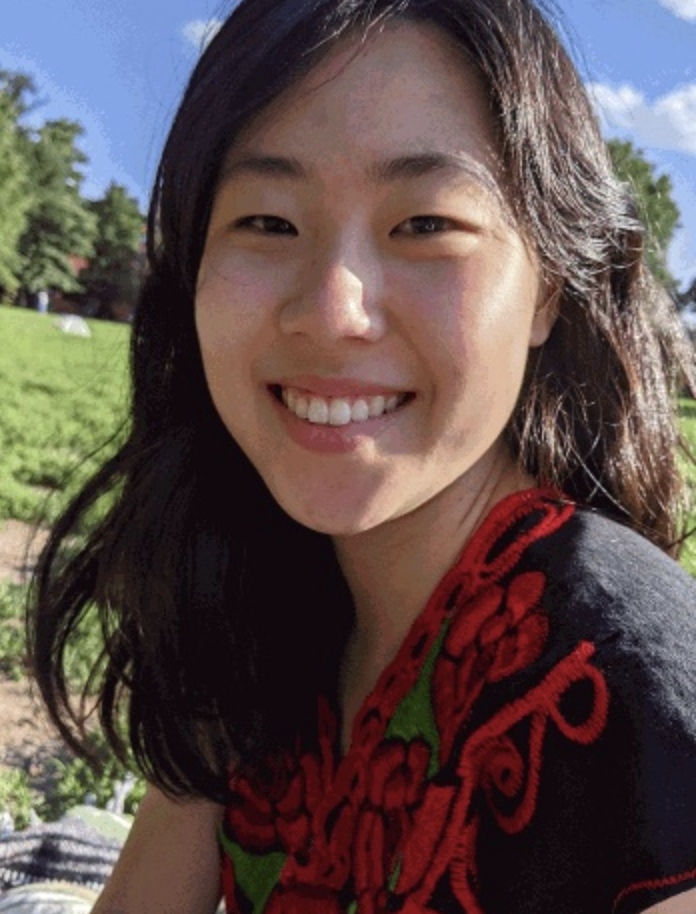

Ceridwen Hall is a poet and book coach. She holds a PhD from the University of Utah and is the author of two chapbooks: Automotive (Finishing Line Press) and Excursions (Train Wreck Press). Her work has appeared in TriQuarterly, Pembroke Magazine, Tar River Poetry, The Cincinnati Review, and other journals. You can find her at www.ceridwenhall.com

Trees

Cottrell had decided to continue his convalescence by sleeping in the living room downstairs. Now this already felt like a terrible mistake. How often had he bounded up those stairs to fetch a book for Miranda or for no better reason than to change his cuff links? Or tripped down them, tying a careless bow and checking for any clump of whisker he might have missed while shaving his rosy cheek? His latest passage could not have been more agonising had he been brought down one bone at a time. He was still most unwell.

His head contained enough cotton wool to fill a suitcase, or felt like it did. His throat had turned to Velcro and he might have eaten nothing but pins, needles, screws and nails for a week. His eyes had been replaced by chestnuts, still in their spiky green cases, and the air he was breathing was glutinous. It swam around him. Every breath stung his inflamed membranes like nettles. He drew in this viscid stuff, sucking it through his pipes and tubes as though he were drowning in a salty pudding, which, sadly, did not kill him. He was punch drunk. Worst of all, Miranda made believe he was not particularly ill at all. He was pretending, at least exaggerating manically, and she really never thought he would have turned out to be such a baby.

He pulled his kimono more tightly around him. He admired its angry little dragons, bamboo bridges and round-faced smiling maidens, who had never had influenza. He felt hotter than ever, but he had mislaid his thermometer and he knew that any estimation he might venture was entirely untrustworthy unless he could verify it with a machine. He shivered like a snowman, but his forehead burned like bacon.

His bedside lamp was shrouded almost to darkness by the gauzy scarves he had thrown across it, and he held up his medicine bottle to see how much he had left. It shone with a shade of green he could only describe as evil, but he had great faith in it. He screwed off its childproof cap with much strain and after several attempts and touched his tongue, that wrung-out flannel, to the inside of the cap. Reassuringly unpleasant. He was not allowed another dose until seven, by which time it would be light.

Sipping water helped, but he rationed his intake. Expeditions to the bathroom were so draining. He halted for rest after every step, and it was as though he had left all of his internal organs behind him very briefly, and now they crashed back into him as they hurried to catch him up. His brain bounced painfully around his head like a tennis ball in a saucepan.

Aside from this, from all of this, what was really worrying Cottrell right now was the thought of what was going on in that little courtyard he could almost see through the abysmal black rectangle that was the window more or less at the foot of his daybed. He had lived in this house for years but was not sure he had ever been in that courtyard, in what he was pleased to call real life. He supposed he must have been, but it was foreign to him now as though it had only just appeared. There was a substance there. A mass. Bulk. He had never seen it before. What could it be? His mind was a rubble of groggy notions. He had already propped himself up on his aching elbows and alarmed himself with what turned out to be his own haggard reflection. But that black hump. The deformed back of an embittered and physically extremely powerful individual? And the poisonous red glow about its shoulder. He needed it to turn and was desperately afraid that it would. The never-combed mop of the malevolent ginger hunchback? A fox on the water butt avid for carrion? A torch, its naked flame? A man with a fox on his shoulder? The reflection of his own red lamp? He reached out to touch the lamp, and the fox nodded before he could quite do so.

Then the thing outside suddenly reminded him of his old dog, Tikhon, his childhood playfellow, who had gone mad the week before he had been sent away to school, and who had certainly never been in this house. If only Miranda would come, but it was much too early for that lazy girl. It was foggy, so perhaps she would not come at all. The sulphurous fog crept into the house and slithered into Cottrell’s lungs, which seeped like honeycombs.

When he next awoke, he saw that the hunchback was a dustbin with a black plastic bag dumped on top, slumped horribly to one side like a crushed thing. Why could that not have been dropped into the bin, which was never full? No matter, Miranda was here.

Such abounding good health, such youthful high spirits seemed impossible. Cottrell was thrilled to see her and found her ebullience almost unbearable. She flittered about the swollen atmosphere of his sickroom with a flick of her gorgeous tail as though she were a mermaid, that ravenous enemy of all seafaring men. She consulted a mirror briefly, staring into it like a child into a rock pool, surprised and delighted by the urchins, shrimps and pulsing anemones to be found there. She even wore that skirt, narrower at the knees than at the hips. Her little white hands swam about his face, nibbling with bewildering, uncatchable rapidity. She asked him a hundred questions and would not wait for one answer. When she finally sat beside him, she did so as though she were tucking the train of her dress beneath her, when she was doing no such thing. She had no horror of catching his awful disease; she did not believe he was ill.

She teased him deliciously. She knew the names of all the sanatorium-bound hypochondriacs he liked to pretend he resembled, from Mann, Buzzati, Iwaszkiewicz. All his elixirs were placebos. His medicine was alchemy.

- This green gloop?

Cocking her eyebrow.

- Don’t switch that light on. It pains my eyes.

- You like darkness.

He felt so weak that he knew this tiny girl could thrash him if she chose.

She even threatened to eat his cake.

- No, don’t. It will be horribly stale by now.

- Then I’ll throw it away.

- Please don’t. You never know when I might manage a crumb.

The cake had been a gift from his aunt. Sent through the post. That kind heart had not the least idea of his condition, perhaps also did not think him really ill. It had been cut to reveal a solid interior that looked like nothing more than yellow chalk to Cottrell. It was iced, blue and white. It would be served as a slab, not a slice.

- It looks like Miss Havisham’s bridal cake, trilled Miranda. It’s a mouse trap, she added.

- Spiders, said Cottrell. Miss Havisham’s cake crawled with spiders.

He might have said this to deter the girl from even touching it, but he immediately knew he could never eat any of that blue-and-yellow monster himself now. The cake had been a test. When he should finally feel like a piece then he would know he was well again.

What he wanted to say to this wonderful girl was, Let’s stop sparring and be friends.

- I’ve brought you a present, she said.

Sitting on the edge of his bed, she began to tug at a tuft of hair that had escaped from his kimono, just below his throat. She said it was like a real tree glued to a painted landscape. She had a talent for never appearing vulgar regardless of what she said or did. Cottrell began to wonder what his gift might be.

She swam away noiselessly, her footsteps were always noiseless, no matter where she walked or what she wore on her feet, and re-entered bearing a potted plant before her. A handsome plant with vivid broad green leaves and several blooms, fully opened, the size of old pennies, yellow, blue, and edible-looking. Miranda was very pleased with herself and with her plant.

- The pride of the florist. She seemed rather angry with me for taking it away.

- It looks vigorous, said Cottrell. It will be good to live alongside vigour.

- It will remind you of me. I shall put it over here where you will have to get out of bed to look after it.

- I shall water it with my tears.

Miranda looked at him, still holding the plant at arm’s length.

- Yes, she said. You do that.

They discussed Miranda’s plans and her recent activities. Cottrell had been doing nothing but stare out of the window.

- I have been playing tennis. This afternoon I am going to look at pictures and then a swim before dinner.

She glowed. Her skin shone like pearls.

Cottrell thought she might as well talk of mountain-climbing, bare-knuckle boxing and robbing a bank. He couldn’t even manage the dinner. None of this seemed real to him.

When she left him she kissed her fingertips and pressed them to his forehead, making a mocking sizzle noise by hissing through her teeth. She put a little bottle on his bedside table. The red contents of this bottle threw a flickering oval reflection like a winking eye onto the white cloth.

- Almost forgot. Special potion, she said.

- Is that for me or for the plant? Cottrell asked, but Miranda did not reply.

- We’ll share it, he called after her.

His words came out only as a croak. She had gone into a world where he could not follow her.

He stared out of the window. The black shadow of the garden wall was visible through the tangled branches of the trees. He thought of his plant with its flowers of brilliant cheese. He dreamed of Miranda playing tennis underwater, naked, but veiled with flurries of bubbles and foam.

The hours passed. His room was hot. He began to worry about watering the plant. It would not do to neglect it. The flowers were lovely, almost too much so. Might they fall in this sluggish air, the plant become a limp stem hung with limp leaves, or was it a tropical creature? It surely never grew in an English garden. It struck him now that it might not be real. Not that it was a hallucination, but that it was inorganic, synthetic. Artificial was the word. A rubber plant made of actual rubber. Visitors to sickrooms gave artificial plants to save bother. They imply that you are going to be sick for quite a long time. Did Miranda think that? This plant might be evidence. He needed to get a better look at this tantalising vegetation. The distance between him and it was forbidding but staggerable. He might slither there. He inclined in the right direction. Standing upright again felt as easy and natural as turning a cartwheel. He could allow himself to roll from the couch, taking the bedding with him as a precautionary cushion. He turned and slipped in a drift of sheets and blankets. He remembered rolling down sand dunes, with his sister, as a child. He stared, steadied, from the floor, back at the suddenly naked couch. The receding tide had left a bare beach of surprising objects and humiliating stains: wristwatches, thermometers, spoons and coins, which he had almost forgotten losing. But now he could see the plant, touch it even. Next to the plant and near to the cake, at which he glowered without appetite. It shifted on its eight haunches and cracked its stiff knees. A pool appeared to be forming quite near his face, so he raised himself and reached for a leaf. He still didn’t know if it was real. It was one of those sorts of plants.

He put a thumb to the leaf and left a sweaty print on it. It might have been made of wax. A wax exuded by the leaf? Organic? That’s the thing. He smelled his fingers, smelled the leaf. Everything smelled organic to him. He might try tearing the leaf, to see if it would bleed. Blood and tears, that’s the kind of evidence he required. Then there would be another thing healing in the room, or another damaged thing beyond hope of repair. Perhaps a gift of an artificial plant was a magical gesture. The recipient can’t die unless the plant does, but will surely die if it comes to harm. He noticed a mark on the leaf that had already been made, a black spot the size of a shirt button. A blemish, or a mark that looked like a blemish. A corrupted broken blister that resembled a burn from a cigarette end. Was this some weird crypsis? The symptom of a disease or the invasion of a predator, or a deliberately evolved stain, a pre-emptive self-mutilation? Or had Miranda done this, or would she accuse Cottrell, or both? Some creatures, whose camouflage closely resembled leaves, branches, twiggery were marked with what looked like knotholes. There were those who had doubted Darwin because of such things, recoiling from the idea of a mechanical world, detecting an artist’s touch. He would like to compare this damaged leaf with that of another plant, an incontrovertibly real thing. He watched the trees outside disappear into the darkness, the blackness becoming blacker. The air oozed about him, and he fell asleep on the floor.

When he woke up it was light and there was a gentle rain. That felt like a break in things, but he had not forgotten what he had thought or dreamed about as he lay swaddled round the roots of Miranda’s gift. He would walk into the kitchen, open the back door and collect a handful of different leaves from the garden. He broke a crenellation of icing from the cake, thinking the sugar would give him power, but he couldn’t dare to put it in his mouth. He stood. Gravity felt different to what he remembered. His head was too high, as though he had grown since he had last been on his feet. He had a swig of Miranda’s syrup, and it ran through him, reaching his bloodstream without mediation. Perhaps it was for the plant. There was a label on the bottle, but the writing was too small for him.

The kitchen door, the door to the garden, was bolted at the top and locked with a deadlock. The bolt snapped back with a most satisfying click. Cottrell’s first grin for weeks. But he couldn’t turn the key in the deadlock. It had always been awkward. You had to jiggle it, get it just right, and he couldn’t. He put his shoulder to the door and tried again. He was forceful, using all of his little strength. He was gentle, as though bouncing a feather. It was no good. He could imagine telling Miranda in an hour or so and watching her turn the key with one happy twist of her skinny wrists and smiling back at him with glee. He did feel like crying. He looked at his white arm. It was a cartoon arm, without muscles, drawn by a talentless amateur wholly ignorant of anatomy.

There was another way. The cat-flap. Cottrell and Miranda called it the cat-hole. He had no cat, but the previous owner of the house had had one, he assumed. The hole was fixed shut, but he was sure he could open that, reach through it and grab a leaf or two from where many had fallen into his damp courtyard, compare them with the leaves of Miranda’s gift, and then he would know what was real and what was not. He needed to use a butter knife as a lever, but the cat-hole was easy. A tennis racquet, perhaps hers, was propped against the cupboard door and he did think of poking that through the hole to drag the leaves in, but he was afraid of damaging it, if it was hers, and then having to explain that. He would use his cartoon arm.

This was easiest flat on his back, his usual position. He extended his bare white arm through the now broken-open cat-hole into the cold rain. This was unhandy and unpleasant, certainly. His arm was elbow down and palm up, so it was difficult to pick up leaves from the ground, but he managed with some scrambling around. He had to get up and reel in his arm to look at what he had found. This would not do. He had mangled too much of his haul, these were hardly recognisable as leaves, only as the stuff of which leaves were made. He had torn too much in his grappling. Another go.

He was amused by the idea of someone looking into the courtyard from outside and seeing his one pale limb flapping spasmodically through a hole in the door. Equally diverting was the idea of someone coming into the house, which could only be Miranda, and seeing him lying on the kitchen floor. She would assume that a predatory cat had pulled him from his couch, dragged him into the kitchen, and was now trying, hopelessly, to haul him outside via the cat-hole. For the first time he thought he was definitely getting better.

Now he got a decent leaf. Red, roughly starfish-shaped, very wet and, dismayingly, rather leather-like to the touch. This must be an authentic leaf, but it looked and felt less real to Cottrell than the leaves of his indoor plant. Another leaf had rotted to a network of champagne-coloured lace, the sort of thing from which marvellous underwear might be made. Another was three-toed, the footprint of some unlikely animal. He also pulled in a snail by accident, which sucked itself back patiently into its lovely shell, amber and grey. He rolled that back outside, carefully. More evidence was necessary.

A proper handful this time, but, if anything, more perplexing. This was surely a hornbeam leaf, with its terminal point like a beckoning finger, and this a walnut. There were no such trees in his modest garden. Where could they have blown from?

Now he plunged his arm outside with the reckless determination of the realist’s ambition, the well man’s ambition, to force the world to admit that it is not the place it pretends to be. It was at this point that the truly terrible thing happened to him. He twisted through that difficult torque, unlocking that rusty watch and ward of sinew and bone that he knew he must never unfasten. He heard the sickening click of slipping cartilage that meant he had dislocated his shoulder. This had happened to him several times before, but not for a long time and never while he had had his arm thrust through a cat-hole. He remembered the posture he had to adopt to avoid the real agony, and he did that quickly. His poor arm felt as boneless as a grub. The cat-hole’s little door had fallen in such a way that pulling his arm free would be like pulling his arm off. The rain turned to sleet.

He rolled onto his side, facing the door, and resigned himself to ridiculous catastrophe. What an absurd position, but more than this a number of other things began to seem quite preposterous to him: that he might ever have worn cufflinks, a bow-tie, a kimono. Could any of that really be so? His poor mad dog, Tikhon. What sort of dog was he exactly? And Tikhon. Why Tikhon? Then Miranda. Did he really have a lover, who looked like a mermaid, called Miranda? He could hardly think he deserved one.

Enveloped in misery, he lay soaking water from outside through his sponge-like arm and heard a clatter from the other room. An awakening, a stirring, perhaps the beginning of a prowl. An empty phial toppled and struck the cold hearth with a discouraging tinkle. A blank piece of foolscap was scraped uneasily, but with contempt. Surfaces were negotiated by toeless feet, skated across as though they were planes of ice. He knew it was the knock-kneed spider, flexing its many limbs in its yellow-and-blue armour. He had nothing to do but wait until he should feel the first tentative scratch of its wiry caress down the back of his neck.

Robert Stone was born in Wolverhampton in the UK. He works in a press cuttings agency in London. Before that he was a teacher and then foreman of a London Underground station. He has two children and lives with his partner in Ipswich. He has had stories published in Stand, Panurge, 3:AM, The Write Launch, Eclectica, Confingo, Here Comes Everyone, Book of Matches, Punt Volat, The Decadent Review, The Cabinet of Heed, Heirlock, The Main Street Rag, The Clackamas Literary Review, The Pearl River Quarterly, Angel Rust, Lunate and Wraparound South. He has had a story published in Nicholas Royle’s Nightjar chapbook series. Micro stories have been published by Sledgehammer, Third Wednesday, Palm-Sized Press, 5x5, Star 82, The Ocotillo Review, deathcap and Clover & White. A story appeared in Salt’s Best British Stories 2020 volume. He tweets, mostly about stories, @RobertJStone2.

After the Appointment

I look at my mother as though she is

a burning building and I am tasked

to run inside grabbing as much

of her as I can before she is ash and

I am stepping on the singe of memory,

tasked with sprinting into a burning

house, one in which I have lived

forever—nestled into womb, neck,

pulled at loose knuckle skin,

the body that is not yours but is

most of yours or you are of it

how do you choose just what

to hold onto, which parts to gather—

I want to hold all of her, each

Autumn—the sun casting its

slippery sadness over gourds or stone fruit

as we baked crumble which tasted sweet but

sounds now like misery, the decay of each

forgotten day in each mouthful I shove

in, grabbing wet trodden leaves whose

colors are indistinguishable and ruined the

way memory collapses at the edges—so we do

not recall each fine line, the name of the port town

or perfume, just the ache for those smells. I want

to shove you and each moment into a deep

pocket of a skirt I never owned, maybe one

of yours in which I could put your fine script,

the trip to Japan, each shared bowl of smoky

ramen the chef lit on fire which made you scream

and each day before that, even those days you didn’t

show up, those into the pockets, too, because when

we rush, scooping everything, we cannot pluck out

the damp days, so I would run, gasping into that

house on fire, whatever building you are now

becoming—barn, temple, the house we never owned

I will hold my breath, impossibly against

however long is left—how long until we

get there—how long is there until

foundation walls buckle and it’s just us

and anything I have managed into the pockets

of your skirt, the one it turns out—I always

forget—does not have real pockets, only gaping

hidden holes which lead my hands to find my

own skin.

Emily Franklin's work has been published in The New York Times, The London Sunday Times, Guernica, The Cincinnati Review, New Ohio Review, Blackbird, Shenandoah, and The Rumpus, among other places as well as featured on National Public Radio, and named notable by the Association of Jewish Libraries. Her debut poetry collection Tell Me How You Got Here was published by Terrapin Books in February 2021.

Bullet

The bullet came into my mother’s

room: it nestled itself into one

of her coats.

I was the one who found it:

misshapen and gleaming like a

piece of ore.

The bullet traveled just above her

bed. The hole in her wall and

inch wide.

She was targeted in a drive-by

when she was younger. My father

flung her to the floor and shielded

her with his body.

They were robbed at Christmastime

when I was little. The man held

a shotgun to my mother. My father

could do nothing.

Inexplicably, I place a revolver in

my mouth. My finger is on the

trigger. I am seventeen.

How can I explain the terrain

of my mind? The Earth shook,

disturbing placid waters and revealing

subterranean flowers.

J.L. Moultrie is a native Detroiter, poet and fiction writer who communicates his art through the written word. He fell in love with literature after encountering Fyodor Dostoyevsky, James Baldwin, Bob Kaufman, David Foster Wallace and many others. He considers his work to be experiential, abstract expressions.

Encore

I’m pretty much myself in my movies, and I’ve accepted that.

– Steve McQueen

I’m sorry, I didn’t hear you. If you know the movie you want to see, say its name.

I sigh and ask the female robot to repeat the movies playing in Harvard Square.

Are you still there?

“Yes, I’m still here.”

Great! If you know the movie you want to see, say –

“Find a theater.”

Sorry, I didn’t hear you. If you know the movie you want to see, say its name, or say find a–

“Find. A. Thea-ter.”

Great! Would you like to know what’s playing at Loewe’s Harvard Square?

She does this on purpose—withholding information, asking me to repeat myself, testing my decisions. Only after I relax, speak in a calm, even tone is she convinced that I really do want to go to the movies alone.

Pacing our apartment, I throw on several layers of clothing, straighten up, then open the bedroom door. My wife, Vanessa, leans against the headboard, a down comforter pulled up to her waist. She’s surrounded by books: Women’s Reproductive Rights, Intimate Partner Violence, The New Public Health.

“How’s it going in here?” I ask.

“OK.”

“Really?”

“No. I don’t know. I just don’t get what this professor wants from me.”

“Is she giving you a hard time?” I hope my face appears concerned.

“I think so. No one else thinks that, but I do. Whatever. Six months from now it’ll all be over, and I can be myself again.”

It’s not that I don’t care, but I’ve always had a hard time judging my expressions. People say I look angry. They tell me this when I am angry—stepping off the bus after choosing the seat slick with mysterious liquid or spending a Saturday morning in line at the post office—but they also tell me when I walk up to them on a summer afternoon in t-shirt and jeans, looking and feeling like myself instead of the way I do most of the year in Boston, cocooned like the little brother from A Christmas Story.

“So what movie are you going to see?”

“Not sure. Got a few options that start around the same time. See what I’m feeling when I get there.”

“I’m proud of you,” she says, flipping a page.

I laugh. “Why?”

“That you go to movies alone. Some people would feel too self-conscious.”

I bend toward the bedside mirror, study my receding hairline, then pull on my wool hat. “I used to feel that way. But it’s so dark in there, no one knows who I am.”

Piles of dirty clothes and books and papers; I should stay home. No, I already have a plan. I’ve already watched the day in my head; changing plans now would be like lying, pretending the whole day I was the husband cleaning the apartment while my true self went to the movies.

_

I walk through lower Allston, onto Anderson Bridge leading into Harvard Square. The Charles is frozen solid, but maybe that’s not possible; I guess it just looks frozen. Along the bank, wind whips the snow drifts and moves like smoke up over the bridge. As a commuter train blares its horn in the distance, the Bee Gees fade in through the wind. My hunched walk blooms into a rhythmic strut. I shed my itchy overcoat and reveal my leather jacket and red polyester shirt. My notebook becomes a paint can swinging to the beat.

I step through the snow smoke and I’m back in high school, walking the halls alone, ears plugged, mixtapes of my favorite movie soundtracks blasting in my head. Stand By Me, Rocky IV, Saturday Night Fever. Music made moving through school easier, and if I wandered the halls long enough, I could almost believe I was Kiefer Sutherland or Sylvester Stallone or John Travolta. Anyone but me.

I had friends, some I’d known since kindergarten, but they were scattered throughout the social hierarchy. Mainly, it was me, Chris, Will, and Jesse, playing video games and eating bags of Fritos or staying up until dawn describing our ideal selves to strangers on AOL, wondering if the 15/f/San Fran or the 16/f/NYC were lying as much as we were.

For some reason I still don’t understand, I decided to have a party. My parents were going away for the weekend, and isn’t that what cool people did when they had the house to themselves? Throw a rager? I remember people coming up to me the Thursday before: You’re the kid having the party, right? Where do you live? I told them, each time a dim part of me believing that their intentions were good, that my party would finally offer me the chance to form a huge group of friends, to be the P word: Popular.

Did I really believe that? Perhaps I wanted so badly to believe, desperate to host a party like the ones my brother had when he was in high school, the ones I secretly watched videos of in his room when he wasn’t home—heavy metal band set up in our living room, herds of people talking, laughing, smoking, drinking, kissing, dancing, the individual wooden letters of our WELCOME sign on the mantel rearranged to say COME WEL as if it were the party’s slogan.

My brother has, directly, indirectly, but consistently, attempted to make me hip, teach me the code of cool. He used to tell me to get out of the house more, which I translated to you need to use more drugs and have more sex. No argument there. To me, my brother embodied a classic cool— tough, aggressive exterior, an armor of ripped jeans and flannel, loud music and tons of friends and totaled cars and lip curled into a “fuck you” for anyone, everyone. We grew up in the same house, but he tapped into a secret power source, some volatile element in the ground beneath our home. Stoned in his room, organizing his CD collection, he was not killing time before meeting his wild friends in the street; he was charging himself up, draining our collective resources. There was only so much cool to go around.

The day of my party I rushed home, and my brother and I began preparations. Don was twenty-two, in between jobs and colleges and lives, and had returned from art school in California a year earlier. Aside from my brother’s videotapes, my only house party references were 80s movies— rich blonde guys with feathered hair and Polo shirts trying to score with big-boobed girls with tall hairdos. I was filled with a heady sense of anticipation and dread, which manifested in my decision to put nearly every piece of furniture, along with anything breakable in the basement. Don questioned certain items—a ceramic flower pot, a wicker chair, the microwave.

“Basement,” I said.

“The microwave?”

“I don’t know these people, dude. Put it in the basement.”

Sometimes my brother took me to the movies or brought me to high school with him when I was in elementary school. He led me through the halls and into his classes. I was his item in a new version of “Show and Tell.” He showed me to all of his friends, some I’d glimpsed in his party videos. He told me things: Got pics of that chick naked. That dude puked in our backyard. Used to go to Harlem with that kid and buy acid. He told me that they took the train into the city, then the subway, and waited in the park for the dealer to arrive. They wanted to make sure the acid was real, so one of them would try it, not paying the dealer until it kicked in. I believed these stories were part of a true high school experience, that similar adventures were waiting for me, and in a few years, when I finished middle school, I’d unearth my coolness.

__

When I step up to the window and stare at the board of white plastic letters spelling out each movie, each show time, I hear the Fandango voice reading them to me. Say the name of the movie you want… Say the name you want. The woman behind the counter looks up at me with raised eyebrows.

“May I help you, son?”

“One for The Wrestler, please.”

As I walk to the concession counter, I see a heap of tanned, sweaty muscle. Forearms bandaged. Hands limp. Thin blonde hair with dark roots waterfall over his shoulders and face. Stadium lights behind him burn like trains through a fog. At the top of the poster, big white letters shout: “Witness the Resurrection of Mickey Rourke!”

I’ve never witnessed a resurrection before.

__

The sun went down, and I began pacing the house, moving this, adjusting that. Chris, Will, and Jesse arrived, and we sat in my bare kitchen drinking the Coors Light my brother bought for us.

“Jesus, dude. I think you went a little overboard. Looks like you’re moving,” Chris said.

“I’m not taking any chances.”

The music got louder, the towers of beer cans on the table began to rise, and my nerves subsided. I can’t remember who showed up first. But they kept coming. People I’d never seen before showed up drunk, walked like zombies through the front door asking “who lives here?” “Me,” I said the first few times. After a while, I stopped answering.

It’s funny how I can’t remember the most crucial moment. I just remember Jesse’s ex showing up and then we’re drinking and flipping red Solo cups, then we’re stumbling down the hallway, then we’re upstairs, then we’re in my parents’ bedroom, pressed against the door as if barricading ourselves against the muffled shouts and music on the other side.

Time vanished. The sound of cracking wood. I looked out the window and saw close to fifty kids jumping on the deck my father built, a sloppy performance someplace between moshing and brawling. A tough kid named Tom Selleck— I swear that was his name—pushed another tough kid whose name I didn’t know through the deck’s railing and they both crashed to the lawn headfirst. I ran downstairs and saw my brother trying to push his way through the crowd. He turned and saw me and asked where the hell I’d been.

“Fuck this, man,” he said, “I’m calling the cops.”

__

Monday morning, I saw Chris and Will standing by their lockers. I walked up to them and asked what they thought of the party.

“Pretty crazy,” Chris said.

“Yeah,” Will said, glancing over his shoulder.

“What time you guys leave?”

After the cops kicked everyone out, a few friends came back. I passed out with Jesse’s ex while some people were still on the deck. Felt so damn satisfying to be able to think that. Sorry guys, I was busy. I was claiming my coolness, the coolness that lay dormant my first two years of high school.

“I don’t know,” Chris said. “Around two?”

The bell rang, and we headed in separate directions.

“See you guys later,” I said.

I saw them later. Saw them walk through the halls and turn their heads. Saw them sit with Jesse in the cafeteria, as if he were a director, assigning roles to his actors. I saw them every day. But they never said another word to me.

__

As I enter the theater, I think back to when Vanessa and I watched 9 ½ Weeks. Her cousin told her it was “the hottest fucking movie” she’d ever seen. I made popcorn in an oily skillet while Vanessa set up the movie. The DVD menu was grainy, the title hastily scrawled in pink paint over a dreamy Kim Basinger, arms and legs wrapped around a thinner, smoother Mickey Rourke.

Kim Basinger’s hair reminded me of my older cousin’s prom photo, high and wispy. She wore some sort of white, powdery make-up and thick red lipstick. Mickey shoves her against his dining room table, bends her over an untouched meal. Kim fights it. This isn’t a game. She uses all her strength to save herself, to stop him from turning her into who he wants her to be. She slams her fists on his neck, his back, as he forces himself inside her, the muscles of his ass flexing. Kim’s groans are like a death rattle in Mickey’s grip. A shattered vase outlines her body in soaked petals and shimmering glass.

She kisses him.

“Pretty sure that was rape,” I say.

Vanessa shakes her head. “I don’t know what that was.” She grins. “Kinda hot, though.”

I laugh and wonder how getting turned on by Mickey’s rough, no-means-yes approach fits in with my wife’s studies of women’s sexual and reproductive rights. The cool thing to do would be to take her, right here, right now, on top of the throw pillows we bought with a gift-certificate from her mother, kick over the lamp that used to be in her dorm room, tear off my tight thrift-store t-shirt that once belonged to a boy at Magic Circle Day Camp and force myself inside her. Our cat chases the red beads from her broken necklace, then pauses, cocks her head and listens to us gasping, sweating like rock climbers clawing up a ravine without any protection. My neck veins bulge like Stallone’s in Cliff Hanger.

“I can see how that’d be hot,” I say, digging through the popcorn.

_

My feet stick to the floor. An audience of empty red chairs coated in soft light. Down the runway toward the blue screen. Where to sit? Where do I stand the best chance of being alone? Which squeaky seat will be my public sanctuary? In the back where the bad kids will sit, in the middle where the old folks will sit, in the front where the other bad kids will sit? Or somewhere in the dark divide, twenty-something couples, twenty-something friends, the occasional homeless man, the lonely retiree. Which chair will have gum stuck to the arm, Junior Mints mashed on the seat? When will Lurch drag himself down the aisle and sit in front of me? Jabba the Hut slosh in next to me and pull a gooey peanut butter cup out of his folds? Where is the cougher, the sneezer, the nose-blower? The chatterbox, giggle girl, laugh riot. Squeaky sneaker, knuckle cracker, soda spiller, Milk Dud thrower. Booze smuggler. I pick a seat and watch the audience grow around me.

So many shots in The Wrestler are filmed from behind Mickey Rourke—walking into his trailer, walking into the strip club, jogging through the woods—or the first time he appears, in the locker room, shirtless, a thick, wide V hunched on a stool, hacking and wheezing. The kind of cough that has a history, that would make people in a restaurant turn their heads and wonder if they should call for help. Something dislodges. He spits.

I don’t know it at the time, but I’ll soon watch every movie, read every interview. Then I’ll start looking for audiobooks that he’s recorded—anything featuring his voice or his body. I don’t know how to do it any other way. I don’t know how to passively appreciate. It has to be all-consuming, it has to be obsessive, and it has to alienate myself from other people. Because that’s the ultimate purpose, isn’t it? To find new ways to be alone.

__

Prom. Jesse’s ex and I agreed to be in a limo with a group of people she was friendly with, but not friends with. Big difference. She had about the same number of friends I did and they too were scattered over different cliques, even different grades, which was like a different time zone. But she seemed to have a callused exterior that protected something I could not name, and so I believed she didn’t care about friends. I envied her.

On the ride to Manhattan, the other couples, some of them I had never seen in school, chatted and laughed and discussed post-prom plans. Jesse’s ex and I sat close, holding hands, and stared out the window. When we finally arrived, the limo dropped us off on the corner and the group dispersed. Jesse’s ex and I considered walking past the hotel, crossing the street and blending into the massive crowd in Times Square. Perhaps only I thought this. But I didn’t say a word. She grabbed my hand, and I followed her inside.

I don’t remember dancing. I remember the two of us sitting at a table near the window, picking at side salads: two cucumber slices, two slices of red onion, two olives. Every table offered the same salad. I want to say that we were both on the verge of screaming, of saying “fuck this, we’re outta here.” We must have felt an obligation to stay, to force ourselves to enjoy the night, as one does on New Year’s Eve. This day is important. Enjoy it. We convinced ourselves we were doing the right thing, and, whether I realized it or not, I obeyed the lyrics of the Billy Joel song our class voted as our theme: These are the Days to Remember.

Since we didn’t hang out with anyone, planning weekends was easy. Jesse’s ex had a hot tub in her basement. After her mother came down and checked the laundry and then rummaged through the supply closet and then asked if we wanted something to eat and then sat in her robe on the recliner, the three of us gazing at the television like a staring contest, she eventually submitted and went to bed. We flipped through the channels for another fifteen minutes or so, listening to her mother brush her teeth, flush the toilet, and finally shut her bedroom door.

We stripped each other and stood kissing in the cold basement, the television on mute. I stepped my bare feet onto the slick wooden stairs leading up to the hot tub. Jesse’s ex stood behind me, running her red nails around my waist. At the top of the steps, we stood side-by-side staring into the steam. We kissed and sank, the hot water rising up to my throat.

__

Could it really have been so seamless, so unspoken? Did my old friends resist at first, then realize it was easier to go along with Jesse, to chock me up as a traitor? Maybe they didn’t need convincing. I never questioned them. Never once said: Hey, Chris, remember when we watched Stand By Me every day after school in 6th grade, how we ordered boneless spare ribs and beef with broccoli from Lucky Star, paid with money we made raking leaves, brought it back to your basement and started the movie wherever we left off the day before because it didn’t matter, we knew every line, could watch the movie on mute? Do you remember that?

Or Chris and Will, do you guys remember the Wrestlemania parties we had in middle school, Will’s stepfather walking around in tighty-whiteys, how we giggled and Will’s mom bought dozens of McDonald’s cheeseburgers, unwrapped them, cut them in half, and served them on a giant platter and somehow this made them more delicious? Remember how we’d pretend to be Hulk Hogan and give each other his big boot kick? Remember how we slammed each other to the cold basement rug, punished each other into submission, then returned to the couch and sipped Mountain Dew and were friends once more? Do you remember?

Another part of me (my god, how many are there?) wants to believe I am over this, that it is no big deal. High school bullshit. Let it go, man. It was a lifetime ago. I can look back and see that my relationship with Jesse’s ex— something we called love—was immature, premature, and Jesse’s reaction was the same, as was my old friends’ minion-like response to Jesse’s jealousy. But at the time, Jesse’s ex and I said I love you and meant it. It was real. I am no longer friends with Will and Chris, and that is very real.

__

I don’t know what life was like for Mickey Rourke when the spotlight burned out and Hollywood left him to his dark days. From what I’ve read, his story follows a traditional trajectory—arduous beginning, rocket to fame, booze, drugs, sex, car crashes, tell everyone to fuck off, reclusiveness becomes alienation, and suddenly no one cares. If addiction is escape, are actors the ultimate addicts? Not just jonesing for, but transforming into, another life. What do years and years of acting do to one’s sense of self? Does acting cipher from our tank of identity, eventually leaving us bone dry and hollow? I recall interviews with Mickey—strange isolation in his eyes, vacancy in his voice. He seemed to have bled, hemorrhaged on screen after screen, year after year. Only a husk in pancake make-up remained.

Our obsession with actors lives in the illusion of intimacy. We let these people into our homes, they speak only to us. They seem real. We could be friends. No matter how many times they’ve died, they are immortal. And, like many intimate relationships, when they betray us, we relish the opportunity to witness their suffering.

I don’t know who I am on the walk home from the theater. I feel like me acting like me. A method actor. I’ve been studying, living like the person I was, conjuring up the movements, the dialogue, the expressions of the boy in high school. But that boy was acting like someone else, too, so am I now pretending to be someone who was pretending to be someone else?

Perhaps I’m not a method actor, but a method voyeur, so skilled, so entrenched in the viewing that I’ve forgotten how to act. Just act naturally. Just act like yourself. But if I’m acting naturally, acting like myself, I’m still acting. Still performing. But for whom?

__

A few years after college, Chris called my mother to find out where I was living. He wanted to send me an invitation to his wedding. I hadn’t spoken to him in almost a decade. I was on my honeymoon when the invitation arrived at our apartment in Boston. When we returned, Vanessa tore open the envelope.

“You’re not going, are you?”

“Fuck no.”

A couple days before the RSVP deadline, I checked Yes +1 and dropped the card in the mailbox.

At first, I perpetuated a thin lie about how it would be fun to see who got fat, who was balding, maybe some of them already got their girlfriends pregnant. Vanessa knew, knows, me too well. She let me think these things, but part of her must have known I had other motives for attending Chris’s wedding.

I wanted a cinematic climax to our story. Walk in with my long hair and beard—evidence that I had moved away, moved on, was a city guy now, too cool for our hometown—share a few drinks and somehow the subject of high school comes up and I deliver the cool-calm-collected response I had been repeating in my head for years: Hey, no big deal, you guys. Shit happens. And while that may sound like a flippant statement, I had to practice it over and over, resist the urge to ask why, to beg for explanations, to break down and say, “I wish we were still friends.”

No, that’s not accurate. I don’t wish we were still friends. How could I? I don’t even know them anymore. Perhaps we would have drifted apart regardless of what happened in high school. It doesn’t matter. Being friends now is not the answer. I wish we had that time again, wish we could somehow reclaim our junior and senior years, the moment in our youth when all our history, every bike ride and lemonade stand and broken window and stolen beer should have coalesced into a triumphant celebration, topped off with plans to visit each other at college. But we can’t.

During the cocktail hour, I spoke with Chris’s mom and then his dad and they each said it was so good to see me and asked what was new. His father was our elementary school gym teacher. I had great memories of his gym class, but when I saw him, I was taken aback. He still had the same bald head that gleamed like the gym’s floor, but he had grown, sculpted, a thin goatee and dressed like a car salesman. A woman I never met before stood beside him, and when he shook my hand, I noticed he wasn’t wearing a wedding ring.

I saw Will and Jesse, dressed in matching tuxes, and we talked like distant relatives, as if someone had died and our words tip-toed around the subject. In the middle of our conversation, the photographer began corralling the groomsman and a few select friends for a group shot. I backed away.

“Get in, dude!” Chris said, the first words he’d spoken to me in nine years.

I shook my head, smiled.

Will and Jesse nodded, granting me permission.

I looked at Vanessa and she raised her eyebrows. I squeezed in between Will and Jesse, dead center. The photographer squinted through his viewfinder, twisted us into focus, and captured the moment.

__

Into my fifth or sixth drink, I walked with the pack of groomsman over to the reception tent. Vanessa followed behind us. I was calling Will “Beefcake,” partly a reference to the pro-wrestler Brutus “The Barber” Beefcake we watched battle in his basement, but more so highlighting the extra weight Will was sporting. Vanessa told me to stop. I said that he knew I was kidding. You know I love you, right, Beefcake? Vanessa picked up our table number, same number as Will’s and Jesse’s, and we found our seats at the table closest to the bar.

“So, Beefcake. Still playing the drums?”

Will nodded.

“That’s good. Good for you. I’m proud.”

I used to kid around with Will like this in middle school and the rest of the guys would laugh. But now I was the only one who seemed to find it funny. The music got louder and some people made speeches and I got shots for the table. Then I wandered off with a few other guys from high school, leaving Vanessa at the table alone. When I returned and slumped down in the seat, she turned away.

“What?” I asked.

“Nothing.”

I pressed her and she asked me where the hell I’d been for the last hour and that we made a pact not to leave each other alone at this thing, that I knew she didn’t know anybody. And I said I didn’t know anybody either, I don’t know these assholes. You think I’d choose them over you, that’s insane. But if that’s the way you feel, fuck it, let’s leave. Let’s just leave right now.

“Fine.”

“Good.”

Before we left Chris announced that one plate on each table had a star stuck to the bottom. Whoever had it was the lucky winner and got to take home the centerpiece—a delicate glass vase of perennials. Everyone clapped their appreciation. I flipped over my plate, saw the star, and left it upturned on the table, beside the centerpiece.

__

Vanessa and I sat in bed for most of the next morning, talking. Neither one of us fully remembered driving home. I felt anxious. Perhaps it was the alcohol or the lack of sleep. A mixture of paranoia and dread coursed through me, along with some mutated strand of nostalgia.

What was I expecting from the wedding? Was I hoping the violinist would screech to a halt in the middle of the ceremony, all eyes turn to me as I stand and shout: What about me, you fuckers?! Was I really that caught up in the past to ignore the possibility that these guys may have moved on, that they hadn’t been at home stabbing pins into my miniature likeness for the last ten years?

“I didn’t realize you were still so angry about this,” Vanessa said.

I lay beside her without answering, listening to the hum in my head. “I guess I didn’t either,” I said, rising to my feet. The hum intensified and I made a break for the bathroom, dropped to my knees, and emptied myself. I flushed the toilet and watched the contents swirl, diluting more and more with each spin, until the pipe sucked it down. The clean water in the toilet trembled as I braced myself on the seat and stood up.

__

Chris’s basement. A lifetime ago. We dug through paper bags searching for duck sauce while mimicking Stand By Me. Chris was Gordie, if only because they shared the same skinny frame and squeaky voice. With my crew cut and baby fat, I was Vern, whether I liked it or not. But it didn’t matter. We could be any character because we knew every line. We both wished we were one of the cooler actors, River Phoenix or Keifer Sutherland, but those guys were out of our league. Chris and I even knew the lyrics to all the songs playing in the background. But we often turned the movie off after they found Ray Brower’s body because the end was boring to us. Sappy junk about friends drifting apart.

Recently, I forced Vanessa to watch Stand By Me. She thought it was okay. We watched the movie all the way through, past when the kids split up, to the final scene where Gordie is an adult, with a kid of his own. Gordie is a writer. He sits at his computer, typing the last lines of his story. His son knocks on the door, beach towel slung over his shoulder, asking if they can please, please leave now, that he and his friend have been waiting forever. My dad’s weird, the son tells his friend, he gets like that when he’s writing.

Gordie smiles. Watches his son leave the room. Turns back to the screen. Before he types, his smile fades.

I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve.

Jesus, does anyone?

__

I started writing this when I was 25. I’m 38 now, and going back and reading parts of this essay is like looking at an old photo album. The text is sepia toned, but it’s not false. I don’t feel the anger, the ache for my old friends. Those feelings have subsided to periodic curiosity, nothing a little Facebook snooping every few years can’t satisfy. But what still haunts me, what I think is the reason I’ve returned to this material twelve years later, is the lifelong consequences of childhood choices. What decisions will my sons make when they’re ten or fifteen that will change their lives? Could I warn them? Should I?

Instead, I show them The Sandlot, or Honey, I Shrunk the Kids or The Goonies, because baseball, homemade inventions, and a battered former athlete in a Superman shirt are all in my DNA. The boys lean forward, mouths agape, the flickering images reflected in their eyes.

I tell them not to sit too close.

Anthony D'Aries is the author of The Language of Men: A Memoir (Hudson Whitman Press, 2012), which received the PEN Discovery Prize and Foreword's Memoir-of-the-Year Award. His work has appeared in McSweeney's, Boston Magazine, Solstice, The Literary Review, Memoir Magazine, Sport Literate, Flash Fiction Magazine, and elsewhere. He was recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize and his essay, "No Man's Land," was listed as a Notable Essay in Best American Essays 2021. He currently directs the low-residency MFA in Creative and Professional Writing at Western Connecticut State University.

May Blossom on the Roman Road

On the fourth floor

of Amsterdam’s

Van Gogh Museum,

an East Yorkshire Road

meets a Los Angeles sunset,

fever dream of what must be

somebody on the edge of death,

the violence of the green—

like pickle from the bottle.

Clash with orange road

tongue-pucker,

and you get the canvas itself

astonished at its blooming. Like saying,

all in the trees

caterpillars wiggle.

Let’s go mad about it,

cry

like worms about it,

paint a sky so vast

it becomes

a piece of stage

for the willow trees

and nothing else.

Crumpled spiral of meaning.

Try as it might,

it won’t tell me

how to live.

Allison Jiang is an aspiring journalist working in the digital media industry, but poetry has always been the medium she finds she communicates most clearly in. She graduated from the writing seminars program at Johns Hopkins University in 2020, where she was editor-in-chief of the literary magazine Zeniada. To view the painting her poem is about, click here.

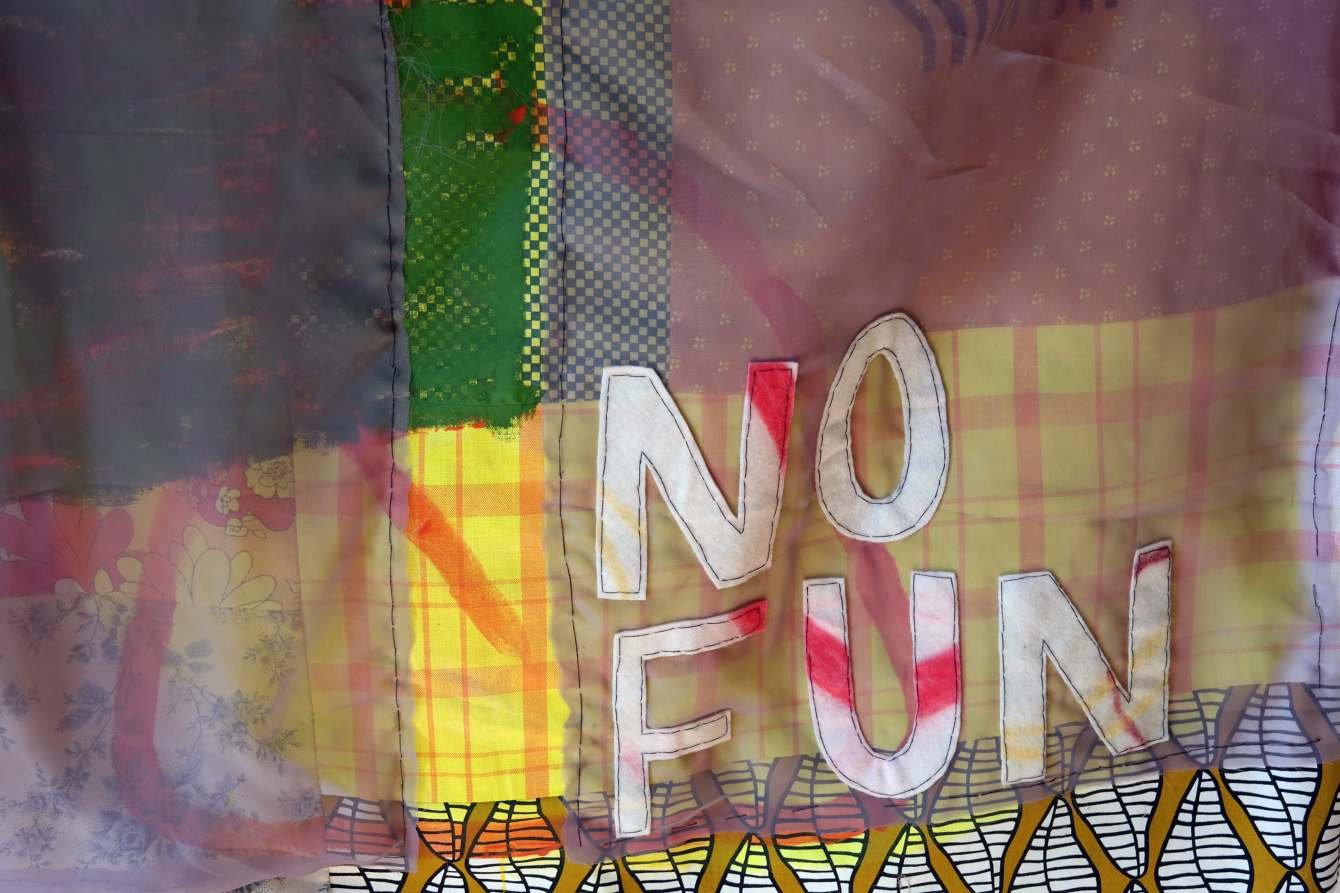

several occupations to consider

my job is to kick dandelions

what's yours? there is no dandelion season

but they arrive most fiercely in the spring.

little bright faces across the grass.

what kind of machine do you dream

of being? i want to be something

compact like a pocket knife

or a button. my dad is a conveyor belt.

i have his eyes & his hands.

have you seen where your parents

keep the capital? mine hide their coins

in eggs & then place the carton

at the back of the fridge. back to

the dandelions. once their seeds are scattered

it's only a matter of time before more

are staring up at you like kittens.

where should we go for dinner?

should we save the spoons &

sleep empty? there is some merit

to skipping every single meal.

well, no actually not but you tell yourself

what you have to in order to survive

sunrise to sunrise. the dandelions

respect me unlike everyone else.

they spit on my boots to shine them

as i explain i only destroy

what i'm told to by my boss.

the dandelions just nod.

is this cruel? it might be.

really i'm helping them.

the wind stopped years ago & they need

to scatter. i'm yearning

for a big forest to get lost in

& never come out. all those

tree mechanisms sprouting

& climbing each other.

i love when people say

"i miss you" when i'm right there.

it's the most honest thing.

i miss you, dandelion faces. i miss you

triumphant circus. drawer of pressed

butterfly wings. where should we

take our rusty springs?

wash them in the river till they

dissolve. i want to be

a dandelion in my next life.

watch myself turn opaque

& fragile waiting for a strong

wind that will never arrive.

Robin Gow is a trans poet and young adult author. They are the author of Our Lady of Perpetual Degeneracy (Tolsun Books 2020) and the chapbook Honeysuckle (Finishing Line Press 2019). Their first young adult novel, A Million Quiet Revolutions, is slated for publication winter 2022 with FSG. Gow's poetry has recently been published in Poetry, New Delta Review, and Washington Square Review. Gow received their MFA from Adelphi University where they were also an adjunct instructor. Gow is a managing editor at The Nasiona.

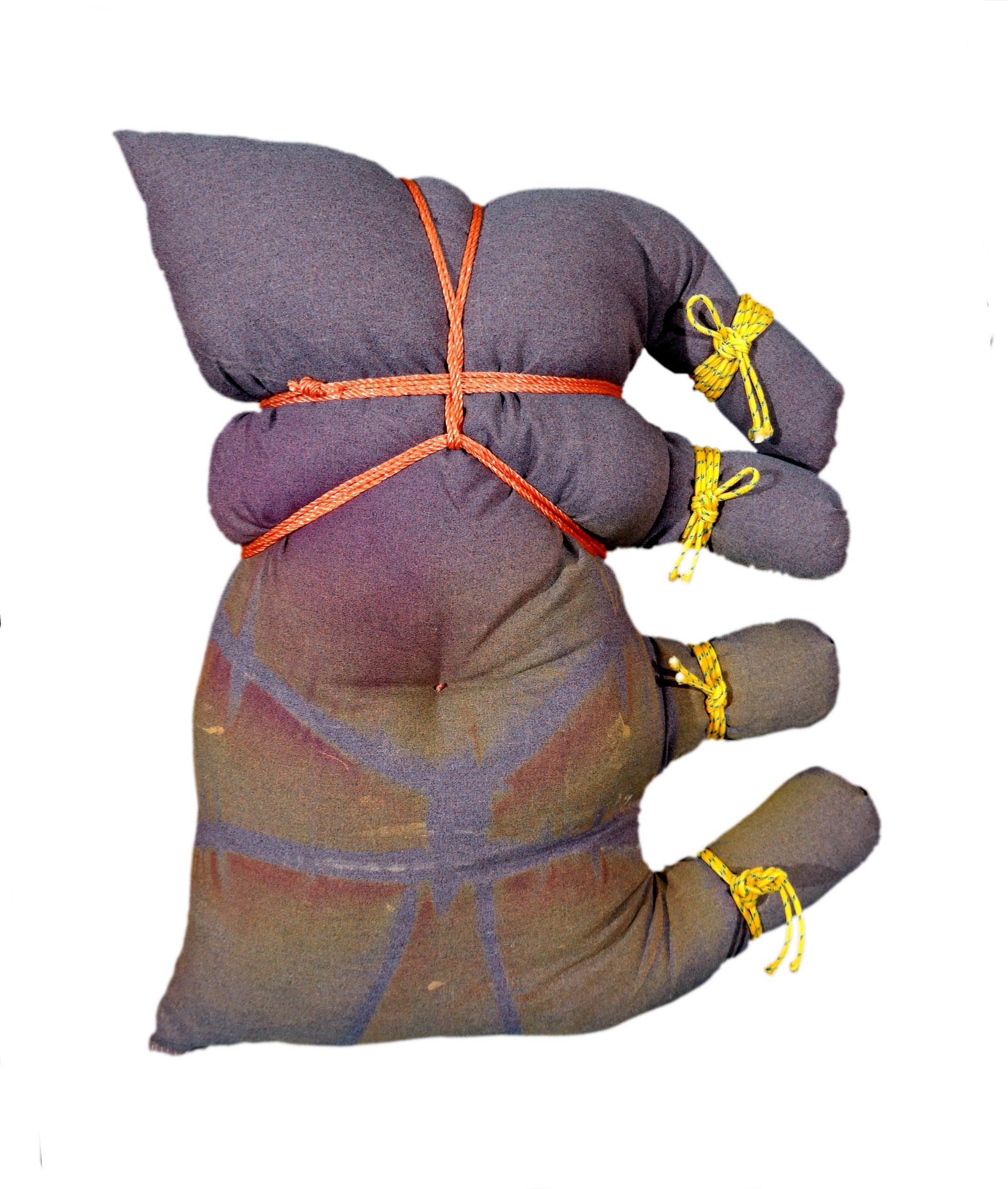

Brain Teaser

(for sk)

If only I could abstract you a bit more. If only you were a wallet photo, a string of code, a dream I forgot after waking. Like Magritte, I cover your face with different objects. Apples. Doves. Flying fish. Like Magritte, I understand a pipe is not a pipe. Hint: you are the pipe. Touch me. Do not touch me. Schrodinger’s cat is both alive and dead as long as the box remains closed. Hint: you are the box. The heart is a lump of tangled legs and matted fur, whiskers trembling on the side of the highway. Red guts along white lines. The brain, like most other organs, never gets the privilege of sunlight. In all that darkness, electricity blooming blue fluorescence. The brain a moon jelly undulating in the thick fluids of the skull. Hint: you are the skull. Cracked open it spills riches, blue yolk sliding in clear viciousness. Beautiful but better left in its shell. The corner of the eye is where most illusions occur. Shadows. Movements. People. Even with the edge of my eye I know your shape. Hint: you are the eye. I gather up your limbs and eyes and buttons. I hold you in the elevator. The man in the elevator asks me what I’m carrying. I say, just some old parts. Yessir, just some old parts.

Kimberly Ramos is a queer Filipina writer from Missouri. They are currently an undergraduate of Philosophy and Creative Writing at Truman State University. Their work has been published in Southern Humanities Review, Jet Fuel Review, and West Trade Review, among others. Their first chapbook, The Beginner's Guide to Minor Gods & Other Small Spirits, is set for publication with Unsolicited Press in 2023.

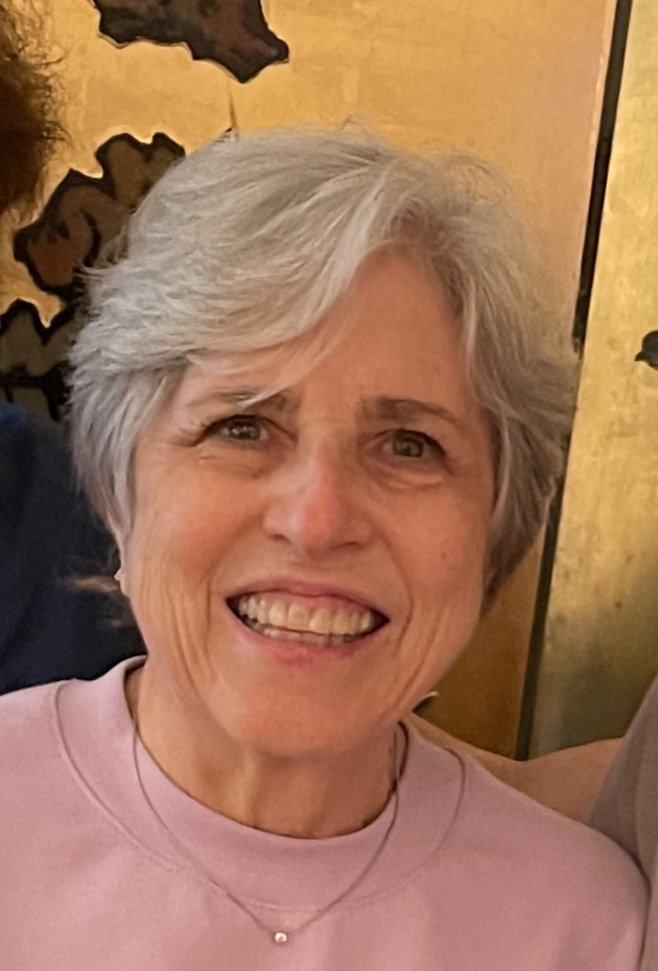

Iowa Through the Windshield

How eerie to deplane in Des Moines, an airport so familiar, and not spot one recognizable face amongst those waiting to collect family or friends. Of course, there would be no welcoming hugs for me—the family members who’d always greeted me had been dead for years. Art and I had flown in from Boston so I could say my last good-byes to the geography of my youth. At least that’s what I told myself. “Do it when you can,” a friend in his eighties cautioned. I had just turned seventy-two, and although I expected to be healthy for another couple of decades, time seemed more finite. I hadn’t been back for sixteen years. In truth, I was homesick.

Visions of Mother, her freshly styled coiffure dyed a pale shade of apricot, spiffed up and dressed in something crisp, a new blouse perhaps, to match her slacks, and of Dad wearing a straw fedora, pacing, chewing on a bit of paper to calm his nerves were etched in memory. My parents would have made the four-hour drive from Ida Grove to collect my son Kevin and me and take us home with them.

My elder sister Kathy who lived in Des Moines would have been waiting too, anxious to see us again in the days when we called ourselves the closest of sisters. She’d be wishing she could have a cigarette. Kathy never lit up if our parents were present— that always made her tense. We had what old-timers called a falling out when our last parent died. After a hiatus of a couple of years, we resumed exchanging birthday and holiday cards, always signed, with love. She didn’t respond when I said I’d like to fly out and visit her, which I took to be her answer. She died six years ago. We never saw each other again.

I reached for Art’s hand, feeling a bit lightheaded as we made our way past the gift store featuring John Deere and Iowa Hawkeye memorabilia. I’d bought a toy tractor there after Mother died, an impulse buy, now a dust catcher in a bookcase at home.

I moved to New York City fifty years ago and have lived on the East Coast since then with no regrets. I visited my parents and sister at least once every year and looked forward to the quiet, to driving through the endless fields of corn and soybeans, the scent of rich, black soil, to sitting on the steps to the back porch, shelling peas for dinner. My immediate family was gone, but I had a few cousins living in the state that I’d not seen in years. I was curious—might I still be family to them, and they to me? I wanted to find out. And I felt the need to reconnect with the countryside of Iowa that I missed.

The itinerary: Six days; eight towns; seven hundred miles of highway.

The last time Art and I visited Iowa and the Sunny Hill Cemetery in Grimes was to bury Dad. The polished pink granite stone, waist-high, modest in design with a sprig of ivy to frame the name, read simply O’Donnell.

My parents’ firstborn, Helen, age three, died of spinal meningitis in 1935. Her small headstone was positioned between our parents. Mother and Dad had laid their headstones to bracket their young daughter’s when hers had been set. Their birth dates were noted, followed by a dash and an empty space. Death was always pending. Even as a young child, I knew my parents would one day be in the ground. Where would I be? Mother’s answer meant to reassure: the plot was big enough for all of us.

Dad and the family made a four-hour drive to visit my grandmother and the cemetery every couple of months. The visits were to tend Helen’s grave. He’d get on his knees to pull weeds and kept a watering can in the trunk of the car. Often it was just the two of us at the gravesite. I’d wander about reading the inscriptions on the stones, careful never to step directly on the grassy mounds so as not to disturb the spirits below.

Dad’s grief over Helen manifested in his fears about safety: “Be careful!” “Watch out!” “See that water? It’s deep. Fall in there and you’ll drown!” Mother shared wistful stories about Helen, how neatly she could eat an ice cream cone when she was only two, how bright and sweet a baby she’d been, but then she’d add, “After she died, I turned myself into steel just to go on living.” As a child, I fantasized that had Helen lived, we might have been a happy, carefree family. Helen was always with us, always missing.

Perhaps Mother wasn’t prepared to be vulnerable again when Kathy was born. “I don’t think I was the right mother for your sister,” she told me. “Even as a baby she’d scream and cry—I was never able to console her.” When Kathy was a teenager, the arguments between them frightened me. Hateful words, threats and always tears until an apology was offered, sincere or not; I trusted neither of them with any details about my life. Their fights continued for decades, often catching me in the middle. That dynamic was motivation for me to move as far from Iowa as I could get.

I paused at the headstones for a last look. There was plenty of extra room here in the Sunny Hill Cemetery as Mother had predicted, but I’d made other plans: Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Cremation for Art and me.

In the afternoon, after I’d paused and taken a few pictures of my grandmother’s house located a few blocks from the cemetery, tidy and looking almost identical to what I remembered fifty years ago, we went in search of my deceased aunt and uncle’s farm. I’d known from an early age that life on an Iowa farm wasn’t for me. The cattle and critters, the physical labor, reliance on the whims of the weather for an income, the isolation of country living, the science of agriculture held no interest. Too soft for farm life, I was a “town girl,” the school superintendent’s daughter who would also be a teacher for a few years, just not one who was attracted to the pick-a-little, peck-a-little gossip and small-town politics that my parents had endured.

Gravel roads got us close to the corn, close to the soybeans; the tires kicked up dust behind us as we traveled. Roads were straight, each one looking like the last, and landmarks were few. I couldn’t find anything familiar, not the farm or the eighty acres that Dad inherited when Grandma died. The anonymous fields stretched without interruption in every direction. We were in the heart of Iowa, the very center of the state. How was it that the land I’d paid so little attention to as a girl brought me, at my age, such joy? There was so much sky. The oyster-grey clouds, others tinged with a bluish purple, were on the move. I could feel the weather in the wind, could smell the storm that threatened but never arrived.

I promised Art the stop at the nursing home in Holstein would be quick. “I just want to say ‘thank you’ again to anyone who might have cared for my parents.” Dad lived in the facility for six years, Mother for four.

“Take whatever time you need,” Art said again, like a refrain. A guy from New Hampshire, my husband hadn’t any experience with the Midwest before we got together. He loved the wide-open vistas, green fields and a horizon that resembled the sea. How many hours had he spent in this parking lot reading the newspaper while I sat with Dad who rarely woke and no longer recognized me? Mother lived in the Loving Care unit, a locked area for residents with dementia and a tendency to wander. Art never knew my parents when they were well. Mother and he would have relished discussing history, like the US involvement in Viet Nam and candidates running for president; Art’s motto, “First, secure the base,” picked up from his days in the army, would have resonated with Dad. It reflected my father’s philosophy about the importance of home.

The sign out front had changed from a picture of hands in prayer to simple text: Good Samaritan Nursing Home. The woman who answered the front door’s buzzer looked at me curiously. “I thought I knew you,” she said when I gave her my name. “Steven and Mildred O’Donnell’s daughter, right?” Dumbstruck to be remembered after a sixteen-year absence, I explained that we were passing through and because the staff had taken such care. My tears welled up. Neither Kathy nor I had been present during our parents’ last days. How could I ever thank the staff that had been there to give them comfort, to report that their deaths were peaceful, whether that was true or not. Good Samaritans indeed, to help the living deal with their guilt as well as their grief.

We were invited to see what had changed. I said hello to the lovely young administrator, commented on improvements to the common areas, peeked into the dining room, and noted that the same aviary in the lobby continued to hold the attention of residents parked there in wheelchairs, as if in front of a TV. I did not walk past Dad’s old room, nor visit the unit where Mother had lived. When I said good-bye, this time I meant it.

Later, unable to sleep, I tossed and turned, cursing the motel’s hard foam pillows. Iowa looked the same, but without my parents and sister, the state seemed empty of love.

My hometown, Ida Grove, was on the itinerary not because any of my close friends from high school still lived there, but because I had fond memories of returning to Iowa with my son and spending a week or two each summer at my parents’ home. Dad bought Kevin a used bike so he could ride around town and to the swimming pool with the neighbor kids, a freedom he never experienced on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. He’d take off after lunch and we wouldn’t see him until suppertime. I left the pressures of my corporate career behind us and would be happy to putter around the house, bake cookies, perhaps work on a jigsaw puzzle with Mother and go to the garden with Dad to pick sweet corn for dinner.

The main street was quiet with more shuttered storefronts than I remembered from sixteen years ago. Only the bank, Christensen’s Funeral Home, and Murray Jewelers looked the same. I didn’t recognize the house at 506 Taylor Street until I saw the carport and trellis. The white paint on my former home had peeled; the lawn was cluttered with random metal-and-wire decorations, birdcages, planters, and a fake wooden gate leading nowhere. The handsome forest green trim and the balcony that stretched the length of the house above the porch were gone. As Art and I stood gawking at the mess, a man approached from the garage out back.

“I used to live in this house,” I said, offering my hand. “Do you mind if I take a few pictures?” Art struck up a conversation as I walked round to the side. Raw wood was exposed under what used to be my bedroom window. Out back, the climbing rose bush that yielded blossoms to decorate my birthday cake each June was gone. The plum tree was merely a stump, and the lilac bushes at the back porch were also gone, as was the cherry tree Dad had planted. I wanted to leave, to erase this mess from my mind and preserve the visage of myself sitting on the porch swing during summer evenings to watch lightening bugs flicker. This was not my father’s house, the one he’d taken such pride in. Any attachment I’d expected to feel toward my former home vanished.

The owner pointed out two men halfway down the block at the curb, talking. “It’s Meryl Miller on the motorcycle, and Corky Brookbank out in front of his house,” he said. “Looks like they want to say hello.”

“We knew it was you,” Corky said when I walked their way. He’d been a rough kid who’d liked to throw snowballs and tease, a boy I’d always avoided. Meryl and his family moved in next door after I went to college. Mother had tutored his son.

“Your old house is looking pretty bad, sorry to say. Your dad always kept it up good.” I nodded, then asked about the neighbors: Larry and Diane across the street—dead; Meryl’s wife, Diane—dead; Mrs. Walker on the other side—gone; Carolyn Burk, once my babysitter—advanced Alzheimer’s, her younger sister, Diane, my playmate— dead; Gerald Schmidt, the trust officer at the bank who I’d planned to stop in and see— also dead.

“It’s the cancer mostly,” Corky said. All these dead people were younger than Art and me. I waved before getting into the rental car, but I didn’t look back at my childhood home.

We drove past the iconic courthouse, a national landmark building where I’d gotten my driver’s license on my sixteenth birthday and first marriage license at twenty-two. I tried the door on the Presbyterian Church, but it was locked.

I expected our visit to Ida Grove would be the centerpiece of the trip. I lived there fifteen years. But having seen my old house and counted up the dead, my hometown felt like a sinkhole. Goodbye to all that.

I’d written my cousins to tell them we’d be visiting and hoped we could get together. We’d seen each other last at Dad’s funeral. Christmas cards were exchanged, but nothing more until I learned about my sister’s death. I needed to explain that I wasn’t at her funeral because neither her husband nor son had called me to say she was sick or that she had died. I’d been shocked to hear the news when a stranger called looking for a phone number, saying he’d tracked me down from my sister’s obituary in the Des Moines Register. I’d been heartsick.

Barb, a second cousin now in her early 60’s, planned a Sunday lunch in our honor, inviting her mother, Norma, and her siblings, Jana and Rick, plus their families. Art and I were on the road early to make the hundred-mile drive from Des Moines to Oakland. Small town folk and farm families were used to traveling long distances by car. It was a straight shot on Interstate 80 to Highway 59.

I noted the healthy-looking fields of soybeans with what appeared to be a bumper crop, and planned to ask Barb’s husband Kim, a farmer about it. Bumper crops sounded like a good thing, but it meant prices would be low due to a glut in the market—was I right about that?

Everyone was seated in the living room, drinking wine by the time we arrived. “These were Grandma Alice’s glasses,” Barb said as she served Art and me.

We were awkward at first and talked about the weather, the drive, how much Des Moines had changed. I’m not sure how we broke the ice—perhaps it was Barb’s delicious homemade apple pie, but before long we regaled each other with tales about our families’ idiosyncrasies.

“Whenever your dad asked me how I was doing in school, I’d just freeze up,” Barb said. My father’s gruff demeanor intimidated most kids, including me. She and Rick described how as kids they’d had to walk the beans in the blazing sun every summer, pulling weeds in the soybean fields. When I asked if they’d been paid an allowance for their labor, they looked at me, astonished, and laughed. “Never.” Didn’t I know my cousin John, their father? No, I thought, with some regret.

I didn’t say it was because I saw how hard my cousins’ lives seemed that I’d decided never to live on a farm.

After lunch, Barb asked if we’d like to take a drive to see the farm. We drove the ten or so miles out of town and parked behind Kim’s pick-up. The new, bright white barn that housed Kim’s horse and farm implements was trimmed in a clear blue to match the sky. It was the prettiest barn I’d ever seen. To honor their father, Barb, Rick and Jana had constructed and hung a barn quilt, a large wooden painting mounted just under the peaked roof. The contemporary-looking star design painted light and dark blue, orange, and yellow had been a collaborative project; they had reason to be proud.

My jaw dropped when I saw the gorgeous, gargantuan yellow combine. Kim explained how he and neighboring farmers worked as a team and shared their equipment. We were full of questions. “Climb on up and see for yourselves,” Barb said.

Kim pointed out the GPS and described how it was used in the fields. “All the comforts of home,” he said, when I asked about the air-conditioned cab that was big enough for the three of us. I held my breath as he backed out of the barn, happy to give a couple of city folk an experience they’d never had, nor were likely to have again.

I couldn’t visualize how the magnificent machine harvested the corn and soybeans, or how it separated the grain from the chaff, but I imagined what it might feel like to be behind the wheel, looking over one’s own fields, feeling pride in the labor and the miracle of a healthy crop.

“Come visit us in Boston,” I said as we’d hugged goodbye. My invitation was sincere. How pleased the older generation, my Aunt Alice and my mother, would have been had they seen what a good time their families had together. We related, not through memories alone, because in actuality we didn’t share that many. But these were my people. We connected in the present —our conversation and questions weren’t superficial— we were reaching to know one another. I wasn’t longing for the past but envisioning a potential future with these cousins.

Our final stop was Spencer. Finally, a small town that looked prosperous; the main drag was lively with shoppers. My cousin James and his wife Judy had lived in Spencer since they were married in the 1950’s, back when the County Fair in Spencer was known for being superior. Perhaps it still was. I’d called James on the day I learned about my sister’s death. “I wondered why you weren’t at the funeral,” he said. “It seemed really odd, but I didn’t like to ask.” This was not an unusual response for stoic Midwesterners. You didn’t poke around in other people’s business if you were brought up properly. James and I had never had a real conversation in person, let alone via telephone, not because we didn’t like each other, but because the men in the family visited mainly with each other, and the women congregated and talked among themselves. I was glad he picked up the phone that day and could give me a few details about my sister: cancer, cremation, and a well-attended family luncheon after the memorial service.

James and Kathy had been the same age, seven years older than I. They had been close while growing up, but he’d known little about my sister’s life during the last few decades of her life. He asked questions; I answered honestly. He wanted to know about the “trouble” between Kathy and our mother. He said he’d never witnessed any of their fights. No surprise. What happened in the O’Donnell family was never to be discussed with anyone, not even close relatives.

“Kathy and I had so many good times together—just the two of us,” I told James. “But if our parents were present, there was always tension.” How sad, that once Mother and Dad were gone, we separated rather than finding comfort in each other. It was a relief to talk about Kathy with someone who had also cared for her. I needed to share my feelings, something I’d missed by not mourning her death with family at her funeral.

As Art and I readied ourselves to leave, James pulled a couple of buckeye nuts from his pocket and put them in my hand. “Supposed to bring good luck,” he said. I slipped them into my purse. I’d loved finding the smooth, rock-hard treasures when I was a girl. We shared a hug. “Come see us in Boston,” I said and waved goodbye. On the plane back to Boston, Art asked me if I’d done everything I’d hoped to do. Yes.

But I wasn’t done with Iowa, or it with me.

My cousin Jana e-mailed me a year after our trip to say that she, her husband and two sons were planning a multi-state tour of New England and asked if we could meet up while they were in Boston. We made the most of the time we had together: snacks on the roof deck of our condo, a lobster dinner and fun playing video games with the two boys.