Tuna Casserole

Tuna casserole perfumed the foyer, like farmyard not fish shack. Tuna à la Midwest, a dish that Simon had grown up with and still encountered now and again in the cafés of Iowa, not to mention the homes, such as this one on Rita Lyn Court. Simon’s home had been turned inside out since Alice died. His many friends studied his loneliness and tried to fix him up, on the neighborly theory that he needed to ‘get out’ and ‘have company.’ So Simon sat across from a tuna casserole and Grace, who had asked if they should say grace before they ate. Simon did not mind. Part of his practice with Alice, a Quaker, had been to have silence before a meal. He, Alice, and Vic would bow heads and clasp hands. When eating with others, he didn’t do this, because professors never would, and he was a professor. Still, it was fine if someone, always someone outside the academy in fact, asked for a blessing of some sort. Grace, a Methodist, was used to such blessings. “Thank you,” she said, after Simon confessed grace could be a nice beginning to the meal.

Grace hung her head low, low enough her hair bun appeared like a doughnut topper. “Oh Lord, bless this food we are about to receive, and make us truly thankful for the abundance you have given us. In your name, Amen.” She raised her eyes and reached for the casserole, saying, “Would you like me to serve you?” For a long time, Grace had not said that to any man, at any meal— not since her divorce. But Grace wanted another man. She wanted a man to talk to and to sleep with. The sooner the better since, she told herself, she was not getting any younger.

Simon took in Grace’s glowing “harvest gold” kitchen from his perch at the dining counter, where he sat on a swivel stool with too high a seat. To feel more secure, he planted his feet on a stool rung. He didn’t mention how strange it felt to be with a strange woman in her, to him, strange home. He looked, not to say stared, at Grace, whom he had never even seen until she threw open her front door this evening. She had salt and pepper hair, a permanent near-smile, a comfortable bottom, and solid shoes on working feet. Her black and white checked blouse, open at the neck, had a slight lace collar. All in all, not what he expected. He supposed that was because she was not like Alice, who was lean, with a dancing mouth and with-it clothes. Simon’s friend Martha, who knew Grace from the finance office at First National, had fixed them up, telling Grace he liked food. As Simon observed his bright green Fiestaware plate, its mound of casserole grew. “Say when,” coaxed Grace, once more dipping a heavy pale plastic spoon into the Pyrex dish.

“When?” Simon asked, returning from his reflections. He realized he owed a response. “Oh, yes, when.” He put up his left hand like a school guard at a crossing. “Looks delicious.” His hazel eyes, peering from behind his round lenses, locked on the dinner pile, which climbed to a peak, steam rolling off. The steam recalled to him the fresh cow pies dropped by his Grandpa Stubager’s dairy cows. Of course, the tuna scent, though equally familiar, was different and sought Simon’s nose like a drone. With a steady gaze, he distinguished noodles withered as old watchbands, then jagged edges of tuna fish bound together in a glacial gray sauce. Remembering the home cooking of his boyhood, he took the sauce to be the concentrate from a can of Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup, something he had not tasted in 30 years. He did not recognize the topping, however. He asked, “What’s the crust?”

Before Grace answered, she wiped her pink hands on her pastel pantry apron, which read, across a robust bosom, ‘Mom in Charge.’ “Why, that’s corn flakes! The recipe in Home Circle suggested cracker crumbs, but I use corn flakes, to give it a special zest.” Simon’s aunts had used rolling-pinned saltines. He ruminated on his abiding aunts, and how they had always been so good to him. Grace even reminded him some of Aunt Millie. Alas, this intrusive vision of Aunt Millie made it hard for him to warm to Grace romantically. He would work on that since, truth told, this was his first local ‘date’ since he’d been dropped by Darla.

His aunt’s tender face left Grace’s, then floated away. Simon raised his fork from the yellow rubber placemat, pried loose a load of casserole, and carried it to his lips. Once inside his mouth, it seared his palate. Holding back a cry, he gulped down the ice water before him, its cubes adrift in a magenta metal tumbler. Grace startled at his gyrations. “Oh dear! I should’ve warned you it’s a little hot; I just ran it through the microwave again.” She began to fan the casserole with a loop-woven potholder, in a well-intentioned, but failed, effort to cool it.

“No worries,” said Simon, wearing a red, strained look. Grace gave him a distressed glance and toyed with her bun. “After all,” he came back, “it is called tuna hot dish.” Grace snickered at this little joke, relieved.

Simon spied an orange paper napkin triangle, lifted it up, and dabbed at his burnt lips. “What’s that come-hither spicy taste?” he ventured, between two long chews. He decided that, with light-hearted banter, he could get through this meal, as he had survived the hockey-puck pork chops his Aunt Millie had lovingly served him.

“Worcestershire sauce, another little secret,” she said, displaying a quiet pride. “My mother always pronounced it ‘War-chest-er,’ but that’s not right. Would you like something else to drink?” She paused. “Coffee or milk?”

“Milk?”

“I usually have milk with supper. Good for the bones, our family practice doc said. Simon, you’re a growing boy, have milk.” She grinned and reached as if to pat his cheek. At the same moment, the kitchen radio sprang to life, announcing “…Buy, Sell or Trade, it’s WMT on the Sixes…” Grace immediately poked the off-button. “Sorry,” she said. “I usually listen for bargains while I eat.” Simon jerked upright on the stool. During dinner, he, along with Alice, had occasionally listened to good music, usually straight-ahead jazz or flute recitals; never did they go bargain hunting.

“Am I a bargain?” asked Simon, making a joke.

“How much you worth?” Grace shot back. They both chuckled.

Simon hoped Grace hadn’t noticed his spinning on the stool, as he wanted to make a good impression. It was longer than he cared to think about, the last time he had had physical contact with a woman of Grace’s bodily presence. And he wished the image of his Aunt Millie would quit popping up. “I’m worth a handful of raisins and a butt of bread every noon for lunch, at least when I’m in Italy pretending to be Shelley.”

“Shelley? Shelley Winters. That famous actress?”

“No, the poet, Shelley.”

“That’s not much to eat, even for a poet. No wonder you’re so thin, Simon,” said Grace. She wanted Simon to eat with gusto, to devour food in large quantities. To her that meant love and health. Her ex-husband Cecil, in the last eight months of their marriage, when he went all quiet and slept in the basement on an army cot, pushed away her home-cooked meals, saying, “I had a porkburger at The Grill.” But he got thinner and thinner. She came to learn that ‘porkburger’ meant he had missionary sex with Jane Meeker at the Lone Pines Motel over in Coralville. Every time Grace had to go to the accounts department, past the bay where Jane worked, she studied her shoes.

Simon had never thought of himself as thin, but he liked for others to see him that way. He dared to believe his Mediterranean cooking did that for him. “Eat my main meal in the evening,” he said.

“You came to the right place.” Her apple-cheeks beamed. She rose up over Simon and her breasts swayed toward him, as she ladled another heap of casserole on his plate. Humming “Seventy-Six Trombones,” she marched across the spick-and-span linoleum to a golden refrigerator, opened it, and a pulled out a gallon jug of milk.

“I buy the gallons. Save nine caps and you get the tenth gallon free. But I don’t like the gallons. I’d rather buy in cartons; they’re easier to hold and fit in the fridge. Do you prefer cartons? Or jugs?” Grace knew this line of questioning was domestic, even mundane. But she couldn’t help it. Cecil never talked about anything, not even small talk, and for her small talk counted. ‘Small talk’s the best pillow for your sorrows,’ her mother had taught her. And she wanted to get Simon on her pillow, somehow, sometime.

“I like jugs.” Simon paused as he wrestled with what he was about to say. “They’re bigger. My son, Vic, drinks so much milk we can’t keep enough in the house. Jugs for me, for sure,” said Simon, following with a playful salute, as if he were in the Boys’ Band of The Music Man. Simon had no idea of his intention, other than to satisfy Grace, who clung to the tactile things of ordinary life.

Grace was kind-hearted, and kindness was scarce in this world. She poured them each a tall glass, as Simon munched away. “Is skim OK? She asked.”

“Yes, fine,” he said, though Simon preferred whole milk. He loved the creamy texture, the clover taste. For him skim milk was chalk water; he loathed it. He could not tell Grace that. He could not disclose that he and Alice built their dinner around some French or Italian recipe they found, preparing it together as an expression of their love. He abruptly stepped down from the elevated counter stool, before it numbed his knees, and limped over to the refrigerator magnets. He studied them while Grace methodically forked up her food. The magnets—cats, dogs, and hearts –took turns holding up shopping lists (long loaf of sandwich bread, peanut butter), postcards (Hi from the Ozarks Julie and Phil), phone numbers (Bridge Club 335-2414). “Your daughter in the picture? Under the candy cane heart. Has her mother’s smile.”

“Yes, that’s Brenda Anne; she made those magnets in her scout troop. I’m Den Mother.” Simon returned to his perch and cleaned his plate in record time. Indeed, he gobbled the last bites so fast they had nowhere to go. He felt stoppered. He began to sip the chalk water Grace had poured, hoping it would open a passageway, unaware of the white moustache forming on his upper lip. She fought the desire to wipe—lick?— the moustache off. Maybe after dinner something ‘would happen,’ she considered, as she began stacking dishes in the sink.

“Let me scrap those plates for you,” said Simon, putting down the milk glass.

“Dirty dishes aren’t fun,” said Grace, before she tossed off her apron and swallowed a last bit of tuna. “Why don’t we listen to music? I got a new jazz CD today at the Cedar Ridge mall; they still have a special section for CDs.” Grace tried to please. She had been without a man in her life for three years. She prayed for this one. She had dabbed Mon Paris behind her ears because Maria at work told her Simon had been to France. She got tingly thinking about that.

“Way cool. Whadya get? Chet Baker?”

“Haven’t heard him. Got a Kenny G. Nice background for talking. The player’s in the living room.” Simon worried. Kenny G did a bad ballroom version of Keith Jarrett. It would put him to sleep, drugged as he was by the mountain of starch he had just ingested.

Grace bent from the waist full over the CD player, gave it a firm hold, and slipped in the disc. “You can sit here.” She patted the cushion next to her on the winged chartreuse couch. Simon took his shoes and socks off to relax his feet, then did as he was told. The tassels around the couch bottom kept bothering his ankles, which ached from the strain of pushing against the lower bar of his supper stool. Grace rubbed her own ankles, out of empathy, he supposed. They began to drift off, under the soporific influence of Kenny G. In the dip of an enchanting instrumental wave, she asked, “Do you drink alcohol?”

Simon, fearing a trick question, answered, “On special occasions, but I don’t need to,” an answer he knew his Aunt Millie would approve.

“I don’t drink but I can dig up a bottle of my ex’s somewhere,” said Grace. He wished she didn’t remind him of a younger version of Aunt Millie.

“I’m not hooked. It’s the milk I’m trying to shake,” said Simon, to lighten his mood.

Grace smiled. “Milk-Shake. I get it! You trying to shake chocolate or strawberry?” She laughed loud and squeezed his shoulder. “Oh, Simon, that’s a good one.” She giggled, her backside rippling his arm as she went by on her way to the ‘mudroom,’ from which eventually came sounds of bottles banging. Back in a huff and puff, she dusted off a two-liter handle of Hawkeye vodka and gave Simon a jelly glass full. The liquid released a clinical odor; not a brand he knew. But then he never drank vodka. In ‘real life’ he favored French Rhônes and wished to God he had brought a bottle along this evening.

“Bottoms up,” said Grace. “Don’t be a prude.”

Not since high school had Simon heard this rationale for some forbidden behavior. To avoid the label ‘prude’ he tossed it all back in two gulps. It burned as much as the casserole, in a different way. Placing the empty glass down on an aluminum coaster, he caught the arm of the couch, gripping it tight until the nausea subsided. “Tickles a bit,” he managed to say. “Thank you for offering it.” He massaged his throat as he spoke.

“Do your ankles still hurt? Mine do. Those counter stools are too high. Let me rub them.” She grabbed his ankles and told him to stretch out on the coach, a move he readily agreed to, given his dizzy state. Once settled, she worked on his ankles and feet.

“Where do you buy gas?” Grace asked, to keep the conversation going.

That was a curveball. “Gas?” he repeated. “I buy gas at the Hilltop Garage, end of Dodge Street. Why?” Simon began to worry that he had somehow offended her. Maybe because he did not eat enough. Maybe because he took his shoes off. Maybe because he almost passed out from the vodka. He speculated.

“Do you pump it yourself?” Grace went on.

“Yes. Unless I’m getting the free car wash that comes when you pay full price.” Where was this leading? Simon thought. The last time he had a conversation like this was with his mother-in-law, whom Alice always sparred with.

“I don’t pump myself,” she said, dabbing with a hankie at a bit of cornflake crust stuck in the corner of her mouth.

“Really. Why?” asked Simon. The topic bored him out of his mind, but he wanted Grace to know she could confide. He wanted her to feel safe with him, for what purpose he did not know. He found her physically attractive, in an adventuresome sort of way. Taken all together, she had a certain majesty. A woman of such robust, geometrically sound, proportions had never taken a fancy to him. Overcome by these random musings and the fumes from the vodka, he fell asleep.

When he woke, he found Grace patiently seated at the end of the coach, admiring him. He took off his glasses, ruffled his curls and moved next to her. By way of friendship, he gently put one arm around her strong back. His other pointed to the living room wall. “That painting. Like a late Renoir, with a refreshing naiveté,” he said, hoping a compliment on her taste in home decoration would reassure her of his sincerity.

“My sister number-painted it. At Kirkwood she took one of those classes, ‘Copy the Masters.’ That’s supposed to be Renoir and his bathing beauties. She has an attic full. Want one? “

“Yes, except I’m short on space. Your sister doesn’t nibble lead chips does she?”

“What a question!” Grace went scarlet and would have fanned herself, if she had had a fan. As it was, one small bead of sweat surfaced on her upper lip.

“Just teasing. Renoir had lead poisoning, from licking the tips of his brushes. That’s why the women he painted became so swirly and pink on the canvas. Hallucinations from the lead. Fascinating how an artist’s illness can shape his art.”

“Please don’t think I’m boring. After going over financial statements all day, I don’t have energy left for the ‘nature of the artist.’ I should, though. But since the divorce…” Grace heard her voice crack, appearing on the verge of tears.

Simon felt responsible for her upset. Why had he teased about her sister? Why the trivia about Renoir? Why couldn’t he just talk about normal things like normal people? He sounded like such a snob, though really he was curious, even if obsessively so. He wanted to get to the bottom of things, to connect with Grace as a new friend, maybe more, but it was rough going. He decided the best course of action was a polite exit. That’s when Grace put his hand on her breast. At first he did nothing, other than note the placement of his hand and its continued presence there, with no effort on Grace’s part to remove it. Then he cautiously kneaded her breast, like fragile dough for a puff pastry, inching his index finger nearer to the nipple, in a circling motion. Oddly, the motion brought back to him his endless hike with Alice up to the Bocca Nuova crater of Mt. Etna, in Sicily three years ago. When, at circle’s end, he touched the tip of her nipple, Grace emitted a contented sound, then suddenly stood up.

“You can pour yourself another drink while I bring in dessert,” said Grace, straightening the front of her blouse and stepping into the kitchen. While she was gone, he worried.

Moments later, dessert arrived, tapioca pudding with vanilla wafers stuck in, like Aunt Millie used to serve. Grace put the bowls on a TV tray, at the side of the couch. She sat back down next to him, as close as could be. Simon sank into the couch pillows, again putting an arm around her.

“How long were you married?” she asked, as she snuggled in.

“Twenty years.”

“Were you much in love?” As Grace mouthed the word “love,” she directed her eyes to a distant place, somewhere in the ceiling lamp, it seemed.

“Deliriously in love. The honeymoon never stopped.” Simon did not initiate conversation about Alice. He knew that people were afraid to talk about death and cancer. But when someone asked him a direct question concerning her illness or their marriage, he always answered. He was proud of her, of what they had built together, and very willing to give it vocal honor.

“You must feel so bad. I wish I could do something. They say time heals all wounds. It healed me from the loss of my father.” Grace wrapped pinkies with Simon, the fingers resting in his lap. There was no movement on the couch, no sound in the room.

Friends always told Simon about the loss of a father or mother, a sister or brother, an aunt or an uncle. They meant to show they were one with him, that since they survived he could, too. He wanted to reply that he had lost half of himself, that none of those relatives mentioned had ever been part of his ‘soul.’ He didn’t say this because it would mean hurt feelings. But the loss of a loving wife was a lingering pain in his heart, one that never seemed any better. “Thank you for your support,” he said to Grace.

“You can talk to me anytime,” she said, pressing his hand. Then, she turned, put her fingers lightly on his cheek bones and kissed his nose. Simon sat still. Grace went on, aligning her lips with his. She licked her lips, then licked his, before she put her tongue between them. Simon loosened his jaw and his mouth, as she pushed ahead. Alice had a great French kiss. So did Grace. Deep and wet and winding. But she was not Alice.

Grace didn’t pull away. Instead, she kept returning that moist, determined tongue. Simon needed a break, to collect mind and body, to decide. He decoupled himself and said, “The dessert looks yummy.”

“We both need a breather,” said Grace, reaching over to the TV tray. “Simon, you’re as tasty as this homemade tapioca.”

With an unsteady hand, he took the bowl she presented him. It spilled all over his lap. “Yikes,” he said. “What a mess I made!”

“You’re covered in pudding!” said Grace. She grabbed a napkin to clean it off, then hesitated.

“At least it’s not tuna hot dish,” offered Simon.

“It’s OK?” ventured Grace, unsure of herself.

“I’m cool as a cucumber,” replied Simon.

Grace burst out laughing and Simon followed suit. They fell to the floor, got in a mutual bear hug, and rolled and rolled over the white shag carpet. Finally, they stopped, got up, and brushed themselves, as if they were cleaning off lint.

That ritual completed, they simply stood facing each other, holding hands. “Sorry, gotta shove off,” said Simon, ending the moment. “Vic will be wanting to tell me about his first hayride. He’s fourteen.”

“Simon, you are a silly boy,” said Grace, before a satisfied smile escaped from her charged face. At the door, she halted Simon, fussed with his coat collar and gave him a generous embrace, nuzzling into his neck. Simon submitted. Grace freed him, then let go a small sob. “We must do this again. I make a mean chicken pot pie.”

“One of my favorites,” said Simon, before walking off the porch into the autumn night. He smelled burning leaves and saw a neighbor raking more into the pile. Children were gathered around with carved sticks, roasting marshmallows and making ghost howls. He recalled what John Donne said: “In heaven it is always autumn.” Simon was not certain how heavenly he felt now. He really wanted to be less lonely, to be as one in love. Grace, despite her tender mercies, had made him feel even more abandoned. It was not her fault. He understood the blame lay with him. More searching was needed to find his own circle of grace, a circle of Alice past and gone, a present ring guiding him with a new light, letting him see far, his burden of sorrow lifted, freely blessed by another because of who he was, who he is.

As for Grace, she was, indeed, in a true state of grace, free from wrongdoing, guiltless, on a brave path to a new future. And she was following that path with more steadfastness, more truth, than he had thus far managed. He looked forward to discussing with her the idle fact that, despite the popularity of tuna casserole in Iowa, the tuna fish itself could not be caught there. But there were plenty of chickens to be caught. They would serve well in the chicken pot pie that he and Grace might eventually share.

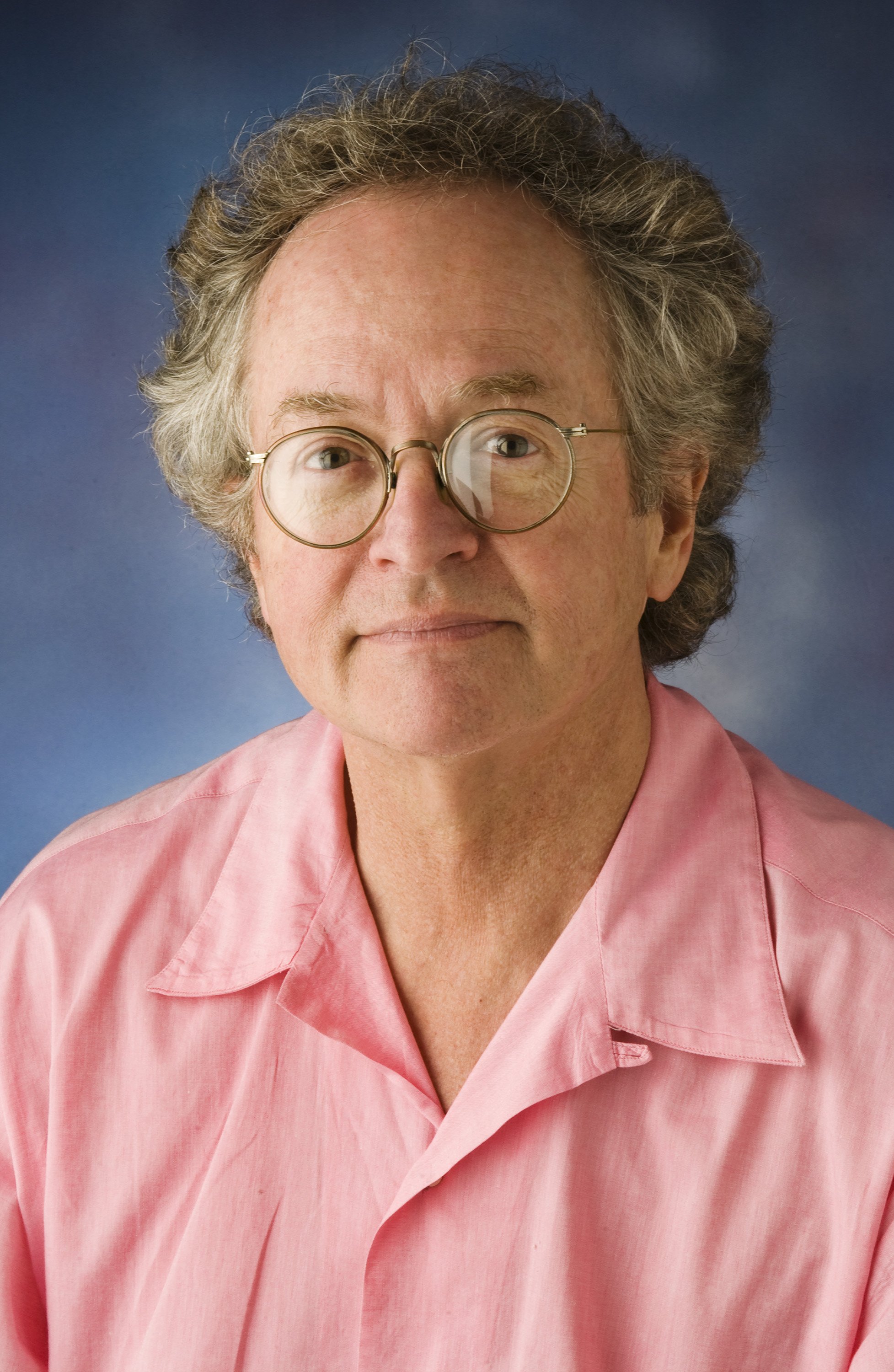

Mike Lewis-Beck writes from Iowa City. He has had pieces accepted for American Journal of Poetry, Alexandria Quarterly, Apalachee Review, Aromatica Poetica, Big Windows Review, Birdseed, Black Bough, Black Coffee Review, Blue Collar Review, Bluestem, Cider Press Review, Columba, Cortland Review, Chariton Review, Eastern Iowa Review, Ekphrastic Review, Frogmore Papers, Guesthouse, Heavy Feather Review, I-70 Review, Inquisitive Eater, MockingHeart Review, Pennine Platform, Pilgrimage, Pure Slush, Rootstalk, Seminary Ridge Review, Southword, the tiny journal, Turtle Island Review and Wapsipinicon Almanac, among other venues. He has two books of poetry, Rural Routes, and Shorter and Sweeter, published by Alexandria Quarterly Press.